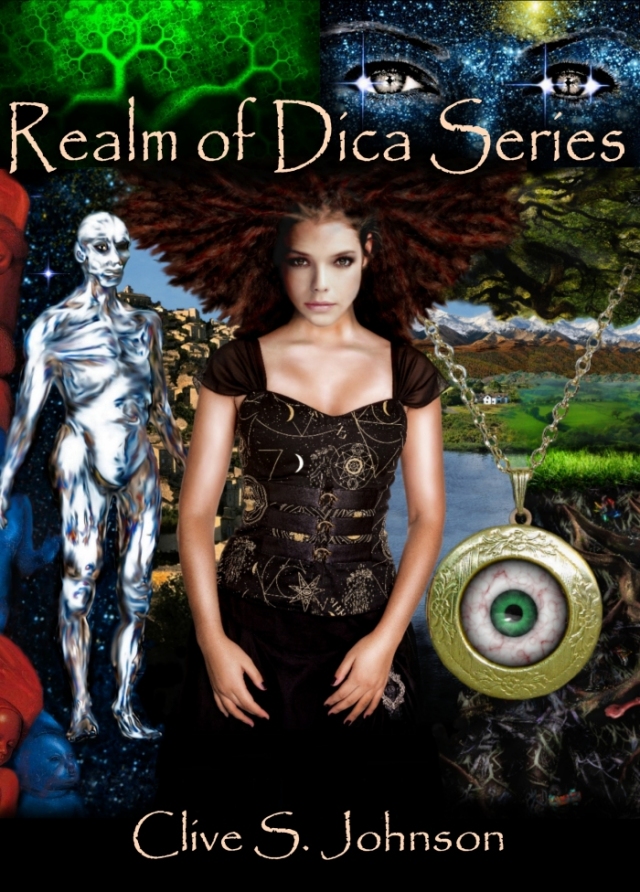

As you can see from the series image cover, The Realm of Dica Series is rich, complex and vast. The covers and artwork are all done by the author Clive S. Johnson. In fact, throughout the print books he has scattered beautiful pencil drawings of his own. Ever since I read and reviewed the first book in this series, Leiyatel’s Embrace, I’ve been wanting to ask Mr. Johnson some questions. So stick around because after my Of Weft and Weave review are some answers I think you’ll find fascinating.

Five Stars for Of Weft and Weave

Clive S. Johnson’s second installment in the Dica series is a delight. It is more fast-paced than Leiyatel’s Embrace with many of the cast of characters of the first novel returning in an attempt to figure out what the heck is going on in their land and is there a way to fix it. Let me state right at the beginning that my heart goes out to Lord Nephril, the long-lived Master of Ceremonies to the many kings of Dica. The journey that takes him from his solitary existence atop the Graywyse Defence Wall to another world in The Lost Northern Way is almost as fascinating as the inner transformation that occurs to him in the process.

Clive S. Johnson’s second installment in the Dica series is a delight. It is more fast-paced than Leiyatel’s Embrace with many of the cast of characters of the first novel returning in an attempt to figure out what the heck is going on in their land and is there a way to fix it. Let me state right at the beginning that my heart goes out to Lord Nephril, the long-lived Master of Ceremonies to the many kings of Dica. The journey that takes him from his solitary existence atop the Graywyse Defence Wall to another world in The Lost Northern Way is almost as fascinating as the inner transformation that occurs to him in the process.

The story opens with the ever faithful and a touch more worldly (at least more so than other inhabitants of Galgaverre) Pettar delivering a mysterious message to Nephril. Mysterious because it is written in the old language, which the aged Nephril can’t recall. In an attempt to decipher it, they cross paths with Steward Melkin. The scene early on with Melkin, and his mind for mechanization, is not only interesting but appears to set a major theme for the novel. When I read it my first thought was, “This is steampunk before steampunk was cool.”

The plot clothes itself in the attire of the expedition. Tolkien springs to mind, though Nephril is neither Bilbo Baggins nor Gandalf, even though I caught myself seeing shades of both from the corners of my eyes. Nonetheless, the adage “the joy is in the journey” certainly applies in this case, particularly with supporting characters with names such as Storbanther, King Namweed, Lady Lambsplitter, Dialwatcher, Breadgrinder, Lord Que’Devit, Steermaster Sconner . . . and the list goes on. In addition to Nephril and Pettar, I have a soft spot for Phaylan and Penolith and, as a wordsmith, appreciate how the soft sound of their names fit their characters.

Some of the plot twists I saw coming, and others I did not, the balance of which made the reading experience even more enjoyable. Speaking of balance, I questioned in my review of Leiyatel’s Embrace how much the author intended the novel to be allegorical. After reading Of Weft and Weave I am further convinced of its allegorical nature given the themes of balance and imbalance, political corruption, death and rebirth, and its apparent nod to the industrial revolution.

It was said of E.B. White that he couldn’t write a bad sentence. Mr. Johnson is one of the few writers I would also put in that category. His flair for detail and description is exemplary. “Like polished slate seen through muslin veils, faint glimpses of torpid sea floated in and out of sight as the swirling mist slowly billowed inshore,” and “He realised she smelt of rose petals and sandalwood, that her skin had a lustre all its own, and her voice a lulling depth that drew tingles to the spine” are but a couple examples (the spelling of realised and lustre being the Brit style, of course).

If you enjoy literary fantasy—and Of Weft and Weave is fantasy, as the limb of Leiyatel would attest—this is the book and series for you. In fact, I purchased the paperback edition and was rewarded, as mentioned earlier, with Mr. Johnson’s fine sketches as well. Of Weft and Weave is a marvelously rich experience that I most highly recommend.

Now an Interview with the author Clive S. Johnson

Thank you, Clive, for agreeing to this short interview. Let’s begin by talking about the title, Of Weft and Weave, and in particular how it relates to Nephril. Not wanting to give away too much of the plot, at one point I was reminded of the shaman’s or wizard’s death. Clearly Nephril is not a wizard, yet to quote Studman, “Father always said [he] created [his] own fair wind. Said it seemed to follow [him] around like a tame bear.”

“No, thank you for asking, Tim.

Well, the title, Of Weft and Weave, has a number of facets, but in the case of Nephril, it refers to the alteration to his structure that was carried out in Leigarre Perfinn, as touched upon in Leiyatel’s Embrace, and from which he gained his immortality, some two thousand years earlier. This alteration gave him a kindred affinity with the preserving power known as Leiyatel, made him a part of her—I can say little more without giving too much away, I’m afraid—and hence why he experiences a “shaman’s death”, as you term it, when he travels beyond her embrace. The protection it has given him up until reaching the Gray Mountains is what was noted by Studman as his father’s reported comment. It may help if I quote from Leiyatel’s Embrace, where Storbanther tells Nephril, in chapter 40 : “You see, Nephril, your having weft and weave of Leiyatel, for your own protection, unbalances everything”.

Of Weft and Weave is also appropriate in the sense of everything being interrelated, co-dependent, that no one part of a world can be altered without affecting the whole fabric, another major and recurring theme of the novel.”

Clive, There’s an interesting exchange between Dialwatcher and Breadgrinder concerning imbalance. Since I refer to the theme of balance and imbalance in my review, would you elaborate on this? After all, Dialwatcher and Breadgrinder appear to live in a very ordered world, one that perhaps once reflected Dica itself?

“You’re right: their small world of Nouwelm is indeed very ordered, and yes, it does reflect what Dica once was long before Nephril was born. The balance referred to is quite simply their taking from Grunstaan—their own smaller version of Leiyatel—no more than what Grunstaan itself can supply in the way of preservation. It’s analogous to our own world’s balance: that we should take no more than can be afforded by the Sun, our own Leiyatel.”

I wrote The Wastelanders out of my concern about the environment. Your work also speaks to me of environmental concerns. Please share why you initially wrote, and continue to write, the Dica series. Was there, or is there, anything in general that spurs you on?

“You’re right to be concerned, as we all should be. But that’s not the nature of our species, nor of life in general—something I address in more detail in the later volumes. As an engineer and a scientist, I’ve known since the ‘70s what course we were set upon, but I also knew that it was something people didn’t want to hear. So it was frustration, really, more than anything, that kept me engrossed in searching out the story of Dica. What every reader says is that “It’s a vividly real place to them”, and that’s because it’s our own world seen through different and perhaps fresher eyes.

On a purely selfish level, that the message hasn’t overpowered the story has given me so much creative satisfaction. In fact, many readers don’t even notice it, which is fine, because a book’s prime justification must be that it’s a damned good read—what all fiction should be. For those who do come away from it with an awareness of its underlying message, I reckon they do so more receptively, not having had it “pushed down their throat”.

What this and my later volumes have allowed me to do, and why there are finally six in the series, is explore the complexities, the contradictions and confusions, the entrenched views and misplaced sentiments surrounding this issue. All the stuff that makes for the messy and confusing reality we now find ourselves in, and for which I’m honest in showing that there aren’t any easy answers—if any at all.”

Readers often see things in a novel the writer may not have realized were in there, Clive. In other words, subconscious messages or themes make their way into a work. I wonder if my interpretation of the Dica series as being allegorical is intentional on your behalf. The reader is seeing a world in transition where the natural and mechanized are melding. What are your thoughts on Of Weft and Weave (and Leiyatel’s Embrace, for that matter) as allegory?

“I’m sure you’re right. I have always tried to be honest in my writing, to explore both weaknesses and strengths both in myself and the world as I see it, sometimes overtly, but I’m sure, often without realising. There’s certainly intentional allegory: my need to express my own views, but also much of my own observations of how our world works—or doesn’t. I think, in many ways, that’s why I relish the created-world genre. It gives so much more scope to come at familiar things from totally unexpected angles, to give a fresh spin on them. And yes, the resurgence of a mechanized world is intentional allegory, but you need to read the next volume, An Artist’s Eye, for more on this.”

Allow me to end this interview on a lighter note, my friend. You are that rare mix, the scientific-artist/artistic-scientist, which brings to mind writers such as Issac Asimov and Alan Lightman. For you, how does the scientist influence the artist? And if you produced a book cover that resembled the Beatles Sgt. Pepper’s album, who would I see in that montage?

“Ha, thanks, and I suppose I am indeed an unfortunately rare specimen in our increasingly specialized world, which has largely lost the Renaissance Man. Leonardo Da Vinci must be spinning in his grave.

I think it’s given me a thirst for knowledge and understanding irrespective of the perceived widely separated camps of artist and scientist. I’m just as fascinated by what a work of art tells me, or a beautiful or ugly view, as I am by a law of physics, and have never been able to see them as different. It’s meant that, for the Realm of Dica series, there’s no traditional fantasy genre magic involved, no wizards and warlocks; everything in the world of Dica is predicated on science—so there’s no convenient plot or narrative get-outs used. It’s all good old Newtonian mechanics with a fair bit of cutting edge quantum physics thrown in, and the whole tale follows a logical progression.

But more importantly, as far as most readers will be concerned, I hope it’s vividly brought alive by my artistic vision, and my artist’s observations. The folk of Dica feel as real as you or me because they’re the product of a lifetime of distilled people watching. And for fiction, that’s what really makes the difference.

As for your last question, well, it would end up being overcrowded, so there’d have to be a cull for the final cover artwork. People who would certainly remain would be—in no particular order—James Lovelock, the originator of the Gaia hypothesis, Mervyn Peake for his superlative Gormenghast trilogy, Gerard Manley Hopkins for his staggering poetry, to whom I’d have to add Shelley, Keats, Browning, Walter de la Mare and a whole host of others, oh, and Emily and Charlotte Bronte, Richmal Crompton of the Just William series, SF authors like Vincent King, Olaf Stapledon, then William Morris, Lewis Carroll, E R Eddison, David Hockney, Ernest Rutherford, Erwin Schrodinger, Thomas Malory, Dickens, Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, William Hope Hodgson, Hermann Hesse, Salvador Dali, Hieronymus Bosch, Albrecht Durer, Tolstoy, Stephen King, Tolkien… Oh, damn; think I’m going to have to start culling again, aren’t I?”

Thank you for allowing us a glimpse into your creative process and creation of The Realm of Dica Series. I look forward to reading more.

And now for all of you who would like to join me in this most intriguing series, here are Clive’s links.

Clive’s website’s “Buy” page, which has all the outlet links.